Voltage divider

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In electronics, a voltage divider (also known as a potential divider) is a simple linear circuit that produces an output voltage (Vout) that is a fraction of its input voltage (Vin). Voltage division refers to the partitioning of a voltage among the components of the divider.

The formula governing a voltage divider is similar to that for a current divider, but the ratio describing voltage division places the selected impedance in the numerator, unlike current division where it is the unselected components that enter the numerator.

A simple example of a voltage divider consists of two resistors in series or a potentiometer. It is commonly used to create a reference voltage, and may also be used as a signal attenuator at low frequencies.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] General case

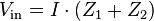

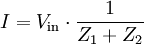

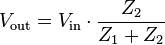

A voltage divider referenced to ground is created by connecting two impedances in series, as shown in Figure 1. The input voltage is applied across the series impedances Z1 and Z2 and the output is the voltage across Z2. Z1 and Z2 may be composed of any combination of elements such as resistors, inductors and capacitors.

Applying Ohm's Law, the relationship between the input voltage, Vin, and the output voltage, Vout, can be found:

Proof:

The transfer function (also known as the divider's voltage ratio) of this circuit is simply:

In general this transfer function is a complex, rational function of frequency.

[edit] Resistive divider

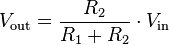

A resistive divider is a special case where both impedances, Z1 and Z2, are purely resistive (Figure 2).

Substituting Z1 = R1 and Z2 = R2 into the previous expression gives:

As in the general case, R1 and R2 may be any combination of series/parallel resistors.

[edit] Examples

[edit] Resistive divider

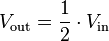

As a simple example, if R1 = R2 then

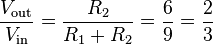

As a more specific and/or practical example, if Vout=6V and Vin=9V (both commonly used voltages), then:

and by solving using algebra, R2 must be twice the value of R1.

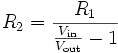

To solve for R1:

To solve for R2:

Any ratio between 0 and 1 is possible. That is, using resistors alone it is not possible to either reverse the voltage or increase Vout above Vin

[edit] Low-pass RC filter

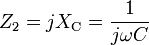

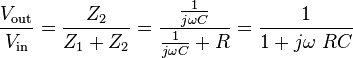

Consider a divider consisting of a resistor and capacitor as shown in Figure 3.

Comparing with the general case, we see Z1 = R and Z2 is the impedance of the capacitor, given by

where XC is the reactance of the capacitor, C is the capacitance of the capacitor, j is the imaginary unit, and ω (omega) is the radian frequency of the input voltage.

This divider will then have the voltage ratio:

.

.

The product of τ (tau) = RC is called the time constant of the circuit.

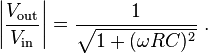

The ratio then depends on frequency, in this case decreasing as frequency increases. This circuit is, in fact, a basic (first-order) lowpass filter. The ratio contains an imaginary number, and actually contains both the amplitude and phase shift information of the filter. To extract just the amplitude ratio, calculate the magnitude of the ratio, that is:

[edit] Inductive divider:

Inductive dividers split DC input according to resistive divider rules above.

Inductive dividers split AC input according to inductance:

Vout = Vin * [ L2 / ( L1 + L2 ) ]

The above equation is for ideal conditions. In the real world the amount of mutual inductance will alter the results.

[edit] Capacitive divider:

Capacitive dividers do not pass DC input.

For a AC input a simple capacitive equation is:

Vout = Vin * [ C1 / ( C1 + C2 ) ]

Capacitive dividers are limited in current by the capacitance of the elements used.

[edit] Loading effect

The voltage output of a voltage divider is not fixed but varies according to the load. To obtain a reasonably stable output voltage the output current should be a small fraction of the input current. The drawback of this is that most of the input current is wasted as heat in the resistors.

The following example describes the effect when a voltage divider is used to drive an amplifier:

The gain of an amplifier generally depends on its source and load terminations, so-called loading effects that reduce the gain. The analysis of the amplifier itself is conveniently treated separately using idealized drivers and loads, and then supplemented by the use of voltage and current division to include the loading effects of real sources and loads.[1] The choice of idealized driver and idealized load depends upon whether current or voltage is the input/output variable for the amplifier at hand, as described next. For more detail on types of amplifier based upon input/output variables, see classification based on input and output variables.

In terms of sources, amplifiers with voltage input (voltage and transconductance amplifiers) typically are characterized using ideal zero-impedance voltage sources. In terms of terminations, amplifiers with voltage output (voltage and transresistance amplifiers) typically are characterized in terms of an open circuit output condition.

Similarly, amplifiers with current input (current and transresistance amplifiers) are characterized using ideal infinite impedance current sources, while amplifiers with current output (current and transconductance amplifiers) are characterized by a short-circuit output condition,

As stated above, when any of these amplifiers is driven by a non-ideal source, and/or terminated by a finite, non-zero load, the effective gain is lowered due to the loading effect at the input and/or the output. Figure 3 illustrates loading by voltage division at both input and output for a simple voltage amplifier. (A current amplifier example is found in the article on current division.) For any of the four types of amplifier (current, voltage, transconductance or transresistance), these loading effects can be understood as a result of voltage division and/or current division, as described next.

[edit] Input loading

A general voltage source can be represented by a Thévenin equivalent circuit with Thévenin series impedance RS. For a Thévenin driver, the input voltage vi is reduced from vS by voltage division to a value

where Rin is the amplifier input resistance, and the overall gain is reduced below the idealized gain by the same voltage division factor.

In the same manner, the ideal input current for an ideal driver ii is realized only for an infinite-resistance current driver. For a Norton driver with current iS and source impedance RS, the input current ii is reduced from iS by current division to a value

where Rin is the amplifier input resistance, and the overall gain is reduced below the gain estimated using an ideal driver by the same current division factor.

More generally, complex frequency-dependent impedances can be used instead of the driver and amplifier resistances.

[edit] Output loading

For a finite load, RL an output voltage is reduced by voltage division by the factor RL / ( RL + Rout ), where Rout is the amplifier output resistance. Likewise, as the term short-circuit implies, the output current delivered to a load RL is reduced by current division by the factor Rout / ( RL + Rout ). The overall gain is reduced below the gain estimated using an ideal load by the same current division factor.

More generally, complex frequency-dependent impedances can be used instead of the load and amplifier resistances.

[edit] Loaded gain - voltage amplifier case

Including both the input and output voltage division factors for the voltage amplifier of Figure 4, the ideal voltage gain Av realized with an ideal driver and an open-circuit load is reduced to the loaded gain Aloaded:

The resistor ratios in the above expression are called the loading factors.

[edit] Unilateral versus bilateral amplifiers

Figure 3 and the associated discussion refers to a unilateral amplifier. In a more general case where the amplifier is represented by a two port, the input resistance of the amplifier depends on its load, and the output resistance on the source impedance. The loading factors in these cases must employ the true amplifier impedances including these bilateral effects. For example, taking the unilateral voltage amplifier of Figure 3, the corresponding bilateral two-port network is shown in Figure 4 based upon g-parameters.[2] Carrying out the analysis for this circuit, the voltage gain with feedback Afb is found to be

That is, the ideal current gain Ai is reduced not only by the loading factors, but due to the bilateral nature of the two-port by an additional factor[3] ( 1 + β (RS / RL ) Aloaded ), which is typical of negative feedback amplifier circuits. The factor β (RS / RL ) is the voltage feedback provided by the current feedback source of current gain β A/A. For instance, for an ideal voltage source with RS = 0 Ω, the current feedback has no influence, and for RL = ∞ Ω, there is zero load current, again disabling the feedback.

[edit] Applications

[edit] Reference voltage

Voltage dividers are often used to produce stable reference voltages. The term reference voltage implies that little or no current is drawn from the divider output node by an attached load. Thus, use of the divider as a reference requires a load device with a high input impedance to avoid loading the divider, that is, to avoid disturbing its output voltage. A simple way of avoiding loading (for low power applications) is to simply input the reference voltage into the non-inverting input of an op-amp buffer.

[edit] Voltage source

While voltage dividers may be used to produce precise reference voltages (that is, when no current is drawn from the reference node), they make poor voltage sources (that is, when current is drawn from the reference node). The reason for poor source behavior is that the current drawn by the load passes through resistor R1, but not through R2, causing the voltage drop across R1 to change with the load current, and thereby changing the output voltage.

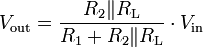

In terms of the above equations, if current flows into a load resistance RL (attached at the output node where the voltage is Vout), that load resistance must be considered in parallel with R2 to determine the voltage at Vout. In this case, the voltage at Vout is calculated as follows:

where RL is a load resistor in parallel with R2. From this result it is clear that Vout is decreased by RL unless R2 // RL ≈ R2 , that is, unless RL >> R2.

In other words, for high impedance loads it is possible to use a voltage divider as a voltage source, as long as R2 has very small value compared to the load. This technique leads to considerable power dissipation in the divider.

A voltage divider is commonly used to set the DC bias of a common emitter amplifier, where the current drawn from the divider is the relatively low base current of the transistor.

[edit] References

- ^ A.S. Sedra and K.C. Smith (2004). Microelectronic circuits, Fifth Edition, New York: Oxford University Press, §1.5 pp. 23-31. ISBN 0-19-514251-9.

- ^ The g-parameter two port is the only one of the standard four choices that has a voltage-controlled voltage source on the output side.

- ^ Often called the improvement factor or the desensitivity factor.

'만들기 / making > senser,circuits' 카테고리의 다른 글

| LED 종류 (0) | 2008.10.01 |

|---|---|

| The NAND gate oscillator (0) | 2008.10.01 |

| 논리회로 연산 (0) | 2008.09.24 |

| electronic circuits (0) | 2008.09.08 |

| 센싱. 과제1) relay에 대한 조사 (0) | 2008.09.08 |